MASTERS ATHLETICS

Annons

Annons

This page contains health information aimed at you who are 35+ and interested in exercise. For more information about the layout of training programs in athletics, we recommend that you contact your local athletics club, as it is difficult to give general recommendations regarding training in athletics. Please read the section on “Planning for training” as the basics of training are the same regardless of age.

In order to feel good physically and mentally, it is important for people of all ages to exercise their muscles, heart and lungs. Regardless of age, it is particularly important to begin training at a duration and intensity appropriate to your current fitness level and then to gradually increase training over time. Varied training can help build coordination, strength and endurance without overloading the body, thus helping to reduce injury risk. Start with basic, all-round training before adding in event-specific training that is appropriate to your goals.

Plan and adjust your training program in relation to your goals and remember to take into account any medical conditions you have. Both strength and aerobic training are effective for older people and it is possible for people of all ages to make improvements using these training types. Remember to plan for the long-term and ensure a varied and balanced diet after training or competitions and do not forget the importance of recovery time!

What happens in the body as we age?

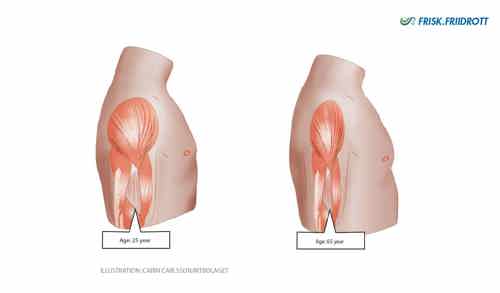

Our bodies reach peak bone mass in our 20s and 30s. Approximately half of this bone tissue is lost by the age of 80. Both bone building and bone degradation take place throughout life and this process is controlled by hormones and influenced by the amount of vitamin D and calcium available in the body. Osteoporosis occurs when there is a persistent imbalance between the breakdown and build-up of bone tissue. The most common form of osteoporosis is caused by a combination of aging, the menopause, genetic susceptibility and unhealthy lifestyle factors such as smoking, physical inactivity and poor diet.

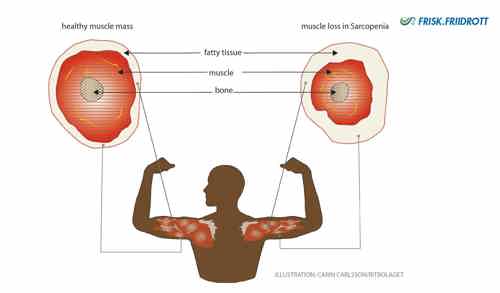

Age-related decreases in muscle mass (sacropenia) are clearly noticeable from the age of 40. After the age of 50 the deterioration in muscle mass occurs more rapidly, with around 12-15% of muscle lost each decade. Fortunately, age-related muscle mass loss can be mitigated by exercise! Muscle cells are divided into 2 types; type 1 fibers and type 2 fibers. Type 1 fibers are ‘slow’ muscle fibers while type 2 are fast and explosive. As we age it is primarily the explosive type 2 fibers that are lost, reducing muscle power, i.e. the ability to use strength quickly.

The muscles are controlled by nerve cells (axons). Our nerve cells’ ability to conduct nerve impulses decreases rapidly with age. In practice this results in a reduction in strength and power as nerve impulses are not conducted at a frequency high enough for older people to fully recruit and coordinate their remaining muscle mass.

Our muscle cells contain special ‘power plants’ called mitochondria that produce the energy the cells need to work. When the muscles work by-products called oxygen free radicals are produced. These substances are extremely reactive and destroy everything that gets in their way. Free radicals harm the mitochondria which causes changes to their characteristics and deterioration in their function. This in turn leads to the production of an even greater number of free radicals. A vicious cycle ensues where increasing numbers of oxygen free radicals destroy various structures in the cells, including the cells’ genetic material. This process is currently the most widely accepted theory to explain aging.

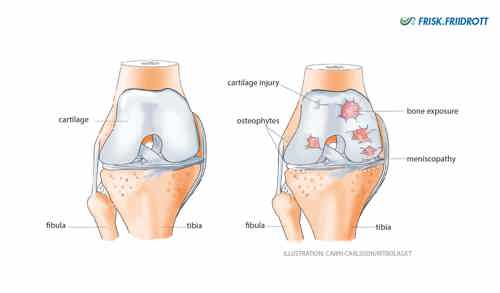

Articular cartilage provides stability and facilitates the smooth sliding of joint surfaces. Healthy articular cartilage has a firm and elastic consistency. Just like bones, cartilage is constantly being built-up and broken down. In the development of osteoarthritis the cartilage is broken down faster than it is built-up. This makes the cartilage thinner and more fragile, cracks can occur in the cartilage and the joint surfaces become rougher creating more friction in the joint. Even the bone that lies under the articular cartilage can be affected by the osteoarthritic process. It is normal for these joints to click and grind and to occasionally feel like they are ceasing up.

Our capacity to absorb and utilise oxygen decreases as we get older. This reduced capacity is mostly due to the fact that our maximum heart rate decreases. The left ventricle of the heart also becomes stiffer, which reduces the stroke volume (the amount of blood that can be pumped out of the heart with each beat). The elasticity of the lungs and chest wall also deteriorates with age which can impair breathing.

Specific physical activity advice for people aged 65 and older:

- The body’s tissues become less elastic with age making it particularly important to warm up before exercise.

- Any increase in physical activity levels should be made gradually and exercise frequency should be increased prior to increasing intensity.

- Regular physical activity is particularly important for older people as it helps maintain functional capacity for everyday life and provides a buffer to cope with life’s fluctuating physical demands.

Styrketräning + 65 år

Studie: Styrketräning med tunga vikter i pensionsåldern kan ha långsiktiga effekter över flera år

I denna studie deltog 451 personer i åldrarna 64-75 år. Sex av tio deltagare var kvinnor. Gruppen delades slumpmässigt in i tre grupper med olika träningsupplägg under ett år:

· Tung styrketräning (HRT): Denna grupp utförde ett övervakat träningsprogram med fokus på hög belastning. Deltagarna tränade tre gånger i veckan på gym och använde maskiner för att utföra 3 set med 6–12 repetitioner per övning på cirka 70–85 % av deras maxkapacitet (1RM). Programmet inkluderade nio helkroppsövningar. Efter en inledande tillvänjningsperiod på 6–8 veckor ökades gradvis belastningen.

· Måttlig intensitetsträning (MIT): Träningen bestod av cirkelträning med kroppsviktsövningar och gummiband tre gånger i veckan. Två pass genomfördes hemma och ett på sjukhuset. Varje övning gjordes i 3 set med 10–18 repetitioner med cirka 50–60 % av maxkapacitet (1RM). Övningarna liknade de i HRT-gruppen, men med lättare motstånd och fler repetitioner.

· Kontrollgruppen (CON): Deltagarna i denna grupp fick inga specifika träningsuppgifter utan uppmanades att fortsätta med sina vanliga fysiska aktiviteter. För att hålla gruppen engagerad erbjöds de regelbundna kulturella och sociala aktiviteter, men ingen organiserad träning.

Efter fyra år hade de som genomfört tung styrketräning behållit sin muskelstyrka

Studien visar att tung styrketräning kan ge långvariga fördelar för äldre personer. Denna typ av träning kan spela en viktig roll i att bevara muskelstyrka och funktion och resultaten ger praktiker och beslutsfattare möjlighet att uppmuntra äldre individer att delta i tung styrketräning.

Vad är ett 1RM?

RM står för "Repetition Maximum," och det anger det maximala antal repetitioner du kan utföra med en viss vikt innan du inte längre orkar göra en korrekt repetition till.

Att räkna ut ditt 1RM (maximala vikt du kan lyfta en gång) kan vara utmanande och riskabelt om du försöker lyfta tunga vikter utan rätt teknik eller säkerhet. Därför använder många en uppskattning baserad på hur många repetitioner du kan göra med en lättare vikt.

Här är ett exempel på en uppskattningsskala:

|

% av 1RM |

Antal repetitioner |

|

100% |

1 |

|

95% |

2 |

|

90% |

4 |

|

85% |

6 |

|

80% |

8 |

|

75% |

10 |

Exempel:

Om du kan göra 8 repetitioner med 40 kg (vilket motsvarar 80% av ditt 1RM), kan du uppskatta ditt 1RM genom att dividera med 0.80:

1RM≈40 kg/0.80=50 kg1RM ≈ 40 \, kg / 0.80 = 50 \, kg1RM≈40kg/0.80=50kg

Tips för att komma igång med tung styrketräning

Att komma igång med tung styrketräning vid 65 års ålder eller äldre kan ge stora hälsofördelar, såsom ökad muskelstyrka, förbättrad balans, bättre bentäthet och minskad risk för fall. Dock är det viktigt att närma sig träningen med försiktighet och korrekt teknik för att undvika skador. Här är några tips för att säkert börja med tung styrketräning om du är 65 år eller äldre:

1. Börja långsamt och öka

Om du är ny inom styrketräning, börja med lättare vikter för att bygga upp en grundstyrka. Fokus bör ligga på korrekt utförande innan du går vidare till tyngre vikter. Tung styrketräning betyder inte att man börjar med tunga vikter – det är viktigt att gradvis öka belastningen.

Ett bra sätt är att öka små mängder vikt varje vecka (t.ex. 0,5-2 kg) när du känner dig bekväm med nuvarande belastning.

Målet är att du efter 3-6 månader kan träna med vikter, 3 set med 6–12 repetitioner per övning på cirka 70–85 % av maxkapacitet (1RM).

2. Fokus på stora muskelgrupper

Prioritera basövningar som aktiverar stora muskelgrupper och förbättrar funktionell styrka. Exempel på övningar som passar:

Knäböj (kan börja med kroppsvikt eller lätta vikter)

Marklyft (anpassad vikt och form)

Bänkpress (alternativ med hantlar för bättre kontroll)

Roddrag (kan göras med gummiband eller vikter)

Axelpress (med hantlar eller maskin)

Utfallsteg (med eller utan vikter)

3. Ge tid för återhämtning

Återhämtningen blir viktigare med åldern. Ge dina muskler tillräckligt med tid att återhämta sig mellan träningspass. Lämpligt att träna styrketräning 2–3 gånger per vecka med vilodagar emellan.

4. Kost och proteinintag

Styrketräning kräver ett ökat proteinintag för att hjälpa musklerna att återhämta sig och växa. Sikta på att få i dig tillräckligt med protein i kosten, såsom från fisk, kyckling, ägg, bönor och mejeriprodukter. Ett vanligt riktmärke för äldre är cirka 1.5 gram protein per kilo kroppsvikt per dag.

Referens:

Bloch-Ibenfeldt M, Theil Gates A, Karlog K, et al

Heavy resistance training at retirement age induces 4-year lasting beneficial effects in muscle strength: a long-term follow-up of an RCT

BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2024;10:e001899. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2024-001899

What do we know about injuries in older athletics athletes?

Research into injuries in master’s athletics is limited. The few research studies that have been conducted vary in their quality. Most studies have only included runners meaning there is a gap in knowledge regarding injuries in throwing and jumping disciplines. Furthermore, many of the research studies performed to date within master’s athletics have predominantly recruited male athletes, making the results harder to generalise.

Current research indicates that a healthy master’s athlete’s risk of injury is relatively low and that the incidence (new injury) of injury in master’s athletics is lower than that reported in younger athletes. Overall, a review of published studies indicated that almost 75% of all injuries in masters’ athletes afflict the lower extremity (i.e. from the hip down). Common sites for injury problems in older athletes are the anterior (front) knee, Achilles tendon and foot. Common diagnoses are Achilles tendinopathy (heel tendon), patellar tendinopathy (tendon below the knee cap), plantar fascia pain, ‘shin splints’ and low back pain.

(Heazlewood I, et al., 2017). Ganse et al. 2014

Osteoarthritis is characterised by pain, reduced mobility and impaired joint function. The cartilage in our joints functions as a shock-absorber. When there is a reduction in articular cartilage that shock-absorbing effect is impaired.

About one in every 4 people in Sweden over the age of 45 has osteoarthritis, making it the most common joint disorder. Osteoarthritis is most common in the hip and knee, but all joints can be affected. The risk of developing osteoarthritis increases with age but the risk is also influenced by obesity, previous injuries and genetics. Work that includes frequent loading of the knees, for example through kneeling or repeated bending, increases the risk of developing knee osteoarthritis. Whilst physical activity, a healthy diet and weight control can all relieve the symptoms of osteoarthritis, physical activity has the greatest pain-relieving effect! Assessment by an Orthopaedic doctor is recommended in cases where, despite appropriate exercise, weight loss and the use of pain-relieving medications, moderately disabling symptoms persist beyond 6 months.

Physical activity can help relieve osteoarthritis related pain through a number of mechanisms. First, increased physical activity boosts the endorphins serotonin and noradrenaline which help inhibit pain in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). Second, exercise helps reduce joint loading by increasing strength, improving muscle recruitment and coordination as well as improving joint health. Third, the nutritional supply to, and transport of waste products from, the articular cartilage is improved.

If you have osteoarthritis and are about to start exercising – remember!

- A physiotherapist can help you get started with a customised training program.

- Begin each workout with a long warm-up at low intensity.

- Use repeated movements to help maintain mobility in the affected joints.

- Walking or jogging longer distances may be easier in shoes that have good shock-absorption.

- Lifelong training is required to help keep symptoms under control and maintain physical capacity!

One 18-year long study showed that runners did not suffer more knee osteoarthritis than non-runners. The study concluded that healthy older people do not need to avoid long-distance running in order to prevent the development of knee osteoarthritis. (Charkravarty et al., 2008).

Both bone building and bone degradation take place throughout life. This process is controlled by hormones and influenced by the amount of vitamin D and calcium available in the body. Weakening of the bone tissue reduces its robustness and increases the risk of fractures. Osteoporosis occurs when there is a persistent imbalance between the breakdown and build-up of bone tissue.

Osteoporosis is caused by a combination of aging, the menopause, genetic susceptibility and an unhealthy lifestyle. Osteoporosis can also be a consequence of treatment with certain drugs, such as long-term use of cortisone. In women, oestrogen deficiency associated with the menopause causes accelerated bone loss. The most common locations for osteoporosis are the wrist, upper arm, vertebra, pelvis and hip. Osteoporosis is diagnosed by measuring bone density.

Studies have shown that it takes at least 6 months of physical activity to see a measurable increase in bone density. Dynamic training is more effective than static training at improving bone health. Exercise such as jogging, jumping and strength/resistance training are recommended. Exercise should ideally be performed at a moderate to high intensity for 30- 60 minutes, 3-5 times per week. Even 15-20 minutes of balance training per day can reduce the risk of falls and fractures. However, it is important to ensure that the amount and intensity of training is individualised.

What happens in our skeleton when we train?

- The mechanical load on the skeleton affects local bone-building cells.

- Hormones such as prostaglandin and local growth factors are released which stimulate the formation of new bone tissue.

- Improved balance and leg muscle strength can reduce the risk of falls and fractures

Health problems and illnesses

The heart and blood vessels respond best to daily, moderate to low intensity aerobic exercise. Beta-blockers are problematic for older athletes as they slow the heart rate and make it difficult, and sometimes even impossible, to raise your pulse sufficiently to perform effective training.

If you take beta-blockers and have difficulty raising your heart rate sufficiently to perform effective training you should consult a doctor and, if possible, switch to a different medication. If you are taking medication that lowers blood pressure, it is important ensure adequate hydration (drinking) during workouts to avoid drops in blood pressure which can cause you to feel faint.

High intensity exercise is important in controlling diabetes as this is the most advantageous type of training for the body’s metabolism. Unlike cardiovascular disease, training every other day is sufficient for a person with diabetes.

It is important that you do not train on an empty stomach and that you have sufficient energy reserves, or even consume energy during training, to avoid drops in blood sugar levels (hypoglycaemia). This is particularly important when training sessions last longer than 40 minutes. If you have been diagnosed with diabetes, it is extra important to balance your diet – exercise – hydration – recovery – and sleep!

If you have asthma, it is extremely important to warm up sufficiently and interval training works best! It is recommended that you do not exercise outdoors when it is too cold as the cold and dry air can trigger asthma attacks.

The colder the air the more problems it causes for asthmatics. Remember to not forget the wind-chill factor! Asthmatics should avoid extreme cold as temperatures below minus 15 degrees Celsius can trigger severe asthma attacks and impair lung capacity for several weeks.

Training in humid, warm air is best for the asthmatic athlete. It can be advisable to use asthma medication before training and competitions, but remember to stick to normal doses as exceeding the prescribed dose can be classed as doping. If you are allergic to pollen, it may be best to exercise indoors during the worst part of the pollen season.

To ensure the most effective training for your lungs it is important to train at the right temperature and air quality. Warming-up and variation in training are also key. Combining upper- and lower-body strength training with aerobic training is effective for people with COPD.

The menopause occurs on average at the age of 51, but it can occur any time between 45 and 57 years of age. A period of 3-4 years of irregular bleeding often precedes the menopause.

Production of the hormone oestrogen is reduced during and after the menopause. Oestrogen has several important functions in the body, such as protecting against the breakdown of bone mass and against the storage of fat in the walls of blood vessels. The reduced levels of oestrogen associated with the menopause mean that bone tissue becomes more fragile, blood fat levels are negatively affected and the body’s fat distribution changes, with more fat being stored around the abdomen. The most characteristic symptoms associated with the menopause are hot flushes and sweating, which affect about 75% of all women. Women with severe sweating and hot flushes often have disturbed sleep, which in turn can negatively affect their well-being and work capacity. Symptoms of hot flushes can be triggered by spicy foods, wine, coffee or stress. Reduced oestrogen levels also affect the mucous membranes of the abdomen, including the bladder and urethra, which become dry and brittle.

Did you know that strength training can help with menopausal problems?

https://liu.se/nyhet/styrketraning-kan-hjalpa-mot-klimakterieproblem

The most common form of urinary incontinence is stress incontinence, which mainly affects women. The pelvic floor’s supporting structures such as the muscles and connective tissue become weaker through aging. Pregnancy, childbirth, oestrogen deficiency and genetics also contribute to the risk of developing incontinence. Stress incontinence can manifest when jumping, lifting, coughing or laughing. Pelvic floor exercises are the primary treatment for stress incontinence.

Pelvic floor training involves both strength training with maximum contractions and endurance training with submaximal contractions.

To find your pelvic floor muscles, follow these steps:

- Lie on your back or side with bent legs, sit on a chair and lean forward, or kneel with your forearms on the ground.

- Breathe normally throughout the exercise.

- Tighten the muscle around the rectum by squeezing as if you were trying to prevent passing wind. Hold the squeeze.

- Spread the squeeze forward and upwards around the vagina and urethra or towards the scrotum and penis. You should feel a small lift upwards and inwards towards the abdomen.

- Hold this squeeze gently for three seconds.

- Release and rest for at least three seconds.

- Notice the difference between tense and relaxed muscles.

Repeat the exercise ten times and the whole exercise three times a day.

Both bone building and bone degradation take place throughout life. This process is controlled by hormones and influenced by the amount of vitamin D and calcium available in the body. Weakening of the bone tissue reduces its robustness and increases the risk of fractures. Osteoporosis occurs when there is a persistent imbalance between the breakdown and build-up of bone tissue.

Osteoporosis is caused by a combination of aging, the menopause, genetic susceptibility and an unhealthy lifestyle. Osteoporosis can also be a consequence of treatment with certain drugs, such as long-term use of cortisone. In women, oestrogen deficiency associated with the menopause causes accelerated bone loss. The most common locations for osteoporosis are the wrist, upper arm, vertebra, pelvis and hip. Osteoporosis is diagnosed by measuring bone density.

Studies have shown that it takes at least 6 months of physical activity to see a measurable increase in bone density. Dynamic training is more effective than static training at improving bone health. Exercise such as jogging, jumping and strength/resistance training are recommended. Exercise should ideally be performed at a moderate to high intensity for 30- 60 minutes, 3-5 times per week. Even 15-20 minutes of balance training per day can reduce the risk of falls and fractures. However, it is important to ensure that the amount and intensity of training is individualised.

What happens in our skeleton when we train?

- The mechanical load on the skeleton affects local bone-building cells.

- Hormones such as prostaglandin and local growth factors are released which stimulate the formation of new bone tissue.

- Improved balance and leg muscle strength can reduce the risk of falls and fractures

Osteoarthritis is characterised by pain, reduced mobility and impaired joint function. The cartilage in our joints functions as a shock-absorber. When there is a reduction in articular cartilage that shock-absorbing effect is impaired.

About one in every 4 people in Sweden over the age of 45 has osteoarthritis, making it the most common joint disorder. Osteoarthritis is most common in the hip and knee, but all joints can be affected. The risk of developing osteoarthritis increases with age but the risk is also influenced by obesity, previous injuries and genetics. Work that includes frequent loading of the knees, for example through kneeling or repeated bending, increases the risk of developing knee osteoarthritis. Whilst physical activity, a healthy diet and weight control can all relieve the symptoms of osteoarthritis, physical activity has the greatest pain-relieving effect! Assessment by an Orthopaedic doctor is recommended in cases where, despite appropriate exercise, weight loss and the use of pain-relieving medications, moderately disabling symptoms persist beyond 6 months.

Physical activity can help relieve osteoarthritis related pain through a number of mechanisms. First, increased physical activity boosts the endorphins serotonin and noradrenaline which help inhibit pain in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). Second, exercise helps reduce joint loading by increasing strength, improving muscle recruitment and coordination as well as improving joint health. Third, the nutritional supply to, and transport of waste products from, the articular cartilage is improved.

If you have osteoarthritis and are about to start exercising – remember!

- A physiotherapist can help you get started with a customised training program.

- Begin each workout with a long warm-up at low intensity.

- Use repeated movements to help maintain mobility in the affected joints.

- Walking or jogging longer distances may be easier in shoes that have good shock-absorption.

- Lifelong training is required to help keep symptoms under control and maintain physical capacity!

One 18-year long study showed that runners did not suffer more knee osteoarthritis than non-runners. The study concluded that healthy older people do not need to avoid long-distance running in order to prevent the development of knee osteoarthritis. (Charkravarty et al., 2008).

Compete as a master athlete – food and antidoping

If you are planning to compete, remember to check out Sweden’s anti-doping website to ensure that your medicines are not doping-classified. Open the red-green list on the website and enter your prescription to obtain immediate information on whether or not your medication is acceptable for use in competition.

For example, insulin is doping-classified and you must apply for an exemption well in advance of competition. Once the exemption is granted you can compete. These doping rules apply to higher level competitions. For fun-runs and lower-level competitions all medications are normally exempted and you can compete as normal.

Generally the answer is no. What constitutes a good diet for a master’s athlete is basically the same as for all other adult athletes. However, there are some additional considerations for the older athlete.

A relatively high metabolism can often be maintained into older age if one exercises regularly. However, metabolism usually decreases slightly with age due to age related changes in body composition, such as reduced muscle mass. For some athletes aging may contribute to a reduction in appetite which in turn leads to inadequate eating and deficiency in energy and nutritional intake.

According to the Nordic nutritional recommendations (NNR, 2012), individuals over the age of 65 (regardless of whether they an athlete or not) should consume between 15 and 20 percent of their total energy intake as protein (compared to younger ages where the recommendation is between 10 – 20 percent). This is because protein degradation is generally faster in older individuals. This relatively higher proportion of protein consumption is therefore recommended in order to maintain muscle mass and health. As a veteran athlete, protein consumption of around 1.5-2 g / kilo body weight is recommended.

Regular exercise, regardless of age, helps maintain a more efficient protein metabolism. It is good to bear in mind that dietary protein contributes to a small increase in energy turnover because the process of breaking down protein “costs more” than the equivalent process for fats and carbohydrates. Protein helps us feel full and helps ensure the preservation of muscles during weight loss.

After the age of 40 bone mass deteriorates in both men and women. The weight bearing and physical loading associated with athletics helps maintain a strong skeleton. However, it is important to ensure sufficient calcium and vitamin D intake, as calcium and vitamin D interact to help maintain bone health. The current recommendation for daily intake of calcium is 800 mg and the recommendation for vitamin D is 10 micrograms. Ensuring sufficient calcium and vitamin D intake is especially important for those athletes whose diets are insufficient in calcium rich (milk / yoghurt / cheese) and / or vitamin D rich foods (egg yolk / fatty fish / vitamin-enriched fats / dairy products).

The menopause is a natural part of aging and an additional consideration for female athletes. Many changes occur during the menopause and menopausal symptoms can vary greatly between individuals. Central to the menopause are hormonal changes (e.g. reduction in oestrogen levels) and these changes affect the body in diverse ways. For example, skeletal breakdown increases, fat may accumulate and fat distribution may change (despite no changes to diet or activity levels), with more fat accumulating around the waist instead of the thighs and buttocks. Some women may experience hot flushes, sleep problems or depression. During this process it is important to listen to the body and mind and to be a little kinder to oneself as many of these symptoms can contribute to a poorer athletic performance.

Podcast tip (in swedish)

Klimakteriepodden med Katarina Woxnerud, avsnitt 202 – Det läcker

Avsnittet handlar bla om läckage, framfall och bäckenbotten. Är knip det som alltid hjälper? Ska kvinnor 50+ inte springa, hoppa, göra situps?

References

References

1177 Vårdguiden (länk https://www.1177.se )

Bellardini H & Tonkonogi M. Senior power – Styrketräning för äldre. SISU Idrottsböcker. 2013.

FYSS (fysisk aktivitet i sjukdomsprevention och sjukdomsbehandling) – Evidensbaserad kunskap https://www.fyss.se

Heazlewood, I. et al. Injury location, type and incidence of male and female athletes competing at the world masters games. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, Volume 20, e51 – e52

Janusinfo Region Stockholm. Riktlinjer för behandling av urininkontinens

https://janusinfo.se/behandling/expertgruppsutlatanden/urinvagssjukdomar/urinvagssjukdomar/riktlinjerforbehandlingavurininkontinens.5.6081a39c160e9b3873180d1.html

Oikawa SY, Holloway TM, Phillips SM. The Impact of Step Reduction on Muscle Health in Aging: Protein and Exercise as Countermeasures. Front Nutr. 2019 May 24;6:75. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00075. PMID: 31179284; PMCID: PMC6543894.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2019.00075/full